Planning Your Business Research

© Copyright Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD, Authenticity Consulting, LLC.

A Field Guide to Nonprofit Program Design, Marketing and Evaluation

Sections of This Topic Include

Also consider

Description

The following information is intended to give the reader some general guidance about planning a basic research effort in their organization. The rest of the information in the section presents an overview of methods used in business, how to apply them, and how to analyze and interpret and report results.

Research Plans Depend on Information You Need and Available Resources

Often, organization members want to know everything about their products, services, programs, etc. Your research plans depend on what information you need to collect in order to make major decisions about a product, service, program, etc. Usually, you’re faced with a major decision due to, e.g., ongoing complaints from customers, need to convince funders / bankers to loan money, unmet needs among customers, the need to polish an internal process, etc.

The more focused you are about what you want to gain by your research, the more effective and efficient you can be in your research, the shorter the time it will take you and ultimately the less it will cost you (whether in your own time, the time of your employees and/or the time of a consultant).

There are trade offs, too, in the breadth and depth of information you get. The more breadth you want, usually the less depth you’ll get (unless you have a great deal of resources to carry out the research). On the other hand, if you want to examine a certain aspect of a product, service, program, eta., in great detail, you will likely not get as much information about other aspects as well.

For those starting out in research or who have very limited resources, they can use various methods to get a good mix of breadth and depth of information. They can understand more about certain areas of heir products, services, programs, eta., and not go bankrupt doing so.

Key Considerations to Design Your Research Approach

Good business research is about collecting the information you really need, when you need it, to answer important questions and make important business decisions. What is the key to doing good business research? To make the best use of your time, get the information you really need, and make the best business decision, consider the following key questions before doing your research:

1. Why am I doing this research? What important decision am I trying to make?

Always have an important decision in mind when you are doing your research. You are too busy to waste time collecting information to help make a decision that is not vital to your business, or worse yet – collecting information with no purpose in mind. With a clear decision in mind, you will be able to keep your research focused.

2. When do I need to make my decision?

Timing is everything in business. Having 60% of the questions answered in time to make your decision is better than having 100% of the answers after the deadline’s passed. But on the other hand, if your important decision really can wait, there’s no sense in rushing into things and acting on less information that you might have been able to get if you had taken your time. So you need to have a clear sense of when you need to make your important decision.

3. What questions do I really need to answer to make my decision? What information do I really need to answer my questions?

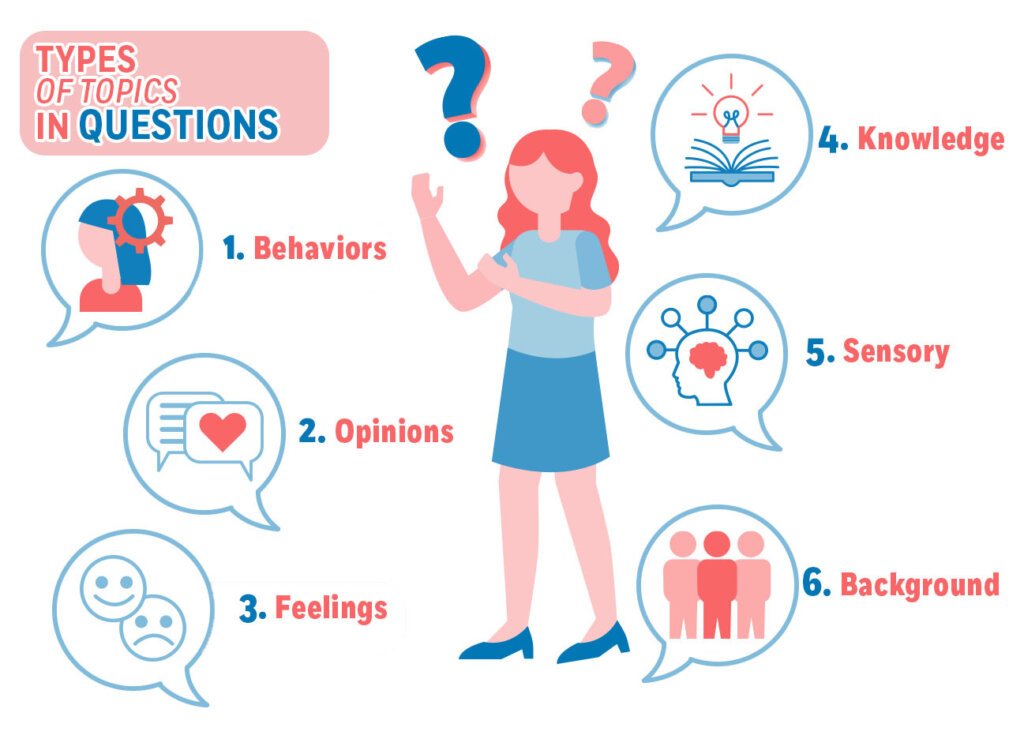

This is where many people get lost in their research. What do you really need to know to be able to make your business decision? Do you need to know a little about a bunch of things, or a lot about a few things? What kind of information do you need? Numbers? Opinions? And how much is enough? (A good rule of thumb is, the more important the decision, the better the information you should collect.) How you answer these questions will have a big impact on where you are going to have to go to get your information, and how you are going to get it.

4. Where is the best place (and who are the best people) to get the information I really need?

Overall, information sources can be broken down into two kinds: primary and secondary. Primary sources are those people and organizations in your marketplace, for example, your potential customers, suppliers, and competitors. Secondary sources are reports, articles, and statistics about the people in your marketplace.

While there are exceptions, it is usually safe to start with your secondary sources, because the information’s usually readily available at low or no cost. Once you have gotten what you can from the secondary sources, ask yourself the question, “Do I really need more information to make my decision?” If you really do, turn your attention to your primary information sources to get the last vital pieces of information you need. But often you can get what you really need from secondary sources.

The real challenge for you with secondary information sources is not having too little information. You will likely be faced with a large amount of information for any decision. The real challenge will be to selectively pick the best from what is available. And it is always a good idea to use at least two good sources of information for any decision, and to make sure that these different sources agree with each other.

If you have done things right up to this point, selecting your sources – primary and secondary – should not be too hard. You will know what decision you are trying to make and when you need to make it, and you will know what information you really need to make that decision. And if you can explain this to the reference librarian at your local library, they will get you pointed in the right direction. It is worth noting that many people go “researching” way before they really know what they are researching – and they waste a lot of time in the process.

5. What options do I have to collect that information?

With secondary information sources, collection is straightforward. You go to the source (library, resource center or website) and ask for the information. With primary information sources, deciding upon the right method is a little more involved. When considering your options, always remember to keep your business decision, timing and the information you really need clearly in your mind. These will help you to make the best decision.

6. What resources do I have to collect that information? Who or what can help me?

You are almost ready to go out and do your research. One final consideration is about the resources you have, or have access to. These resources can include:

- The time you are willing to commit

- Friends and family members who are willing and able to help you

- The money you are willing and able to spend

- Access to the internet, your trainer

- Other resource people in your community like the reference librarian at your local library

7. Given the time, options, and resources I have, what is the best way for me to get the information I need?

Now it is time to make a decision about how you are going to do your research. This is not so much a separate step as it is something that will emerge as you go through the earlier steps. Still, it is good to stop and think it through one last time before you move forward.

8. What am I actually going to do and when?

Okay – it is time to commit to a plan of action. Create a business research action plan to collect your thoughts.

Now you are ready to consider various methods to implement your plan. See Business Research Methods.

9. What ethical considerations might there be in collecting information?

For example, will any of the participants be quoted in research reports? If so, then you should get their explicit information to do that.

Ethics and Conducting Research

Learn More in the Library’s Blogs Related to Planning Business Research

In addition to the articles on this current page, also see the following blogs that have posts related to Planning Business Research. Scan down the blog’s page to see various posts. Also see the section “Recent Blog Posts” in the sidebar of the blog or click on “next” near the bottom of a post in the blog. The blog also links to numerous free related resources.

For the Category of Business Research:

To round out your knowledge of this Library topic, you may want to review some related topics, available from the link below. Each of the related topics includes free, online resources.

Also, scan the Recommended Books listed below. They have been selected for their relevance and highly practical nature.