What Does a Healthy Board Look Like? (Nonprofit and For-Profit)

There has been an extensive amount of research and sharing of opinions about what makes…

Our content is reader-supported. Things you buy through links on our site may earn us a commission

Never miss out on well-researched articles in your field of interest with our weekly newsletter.

Subscriber

There has been an extensive amount of research and sharing of opinions about what makes…

Many people are used to reading or hearing of the moral benefits of attention to…

Business ethics in the workplace is about prioritizing moral values for the workplace and ensuring…

Let’s Start With “What is ethics?” Simply put, ethics involves learning what is right or…

Simply put, strategic planning is clarifying the overall purpose and desired results of an organization,…

Our firm regularly gets calls, asking about the differences between for-profit and nonprofit Boards. Although…

A guest post by Terrence Seamon I recently watched a documentary on TV about the…

This is a guest post from Steven R Roberts Non-Profit Boards, charities, foundations must fight…

How One Typical Facilitator (Mistakenly) Concluded the Client Wasn’t Doing Strategic Planning I got a…

Succession planning is one of the most important topics in nonprofit capacity building. That wasn’t…

Here’s an Example of a Disconnected Conversation A couple of weeks ago, a friend of…

I recently encountered an organization that’s on the cusp of a big change … a…

We often generalize leadership and skills to be the same traits needed all the time…

As a consultant, your perception of project “success” is the basis from which your client…

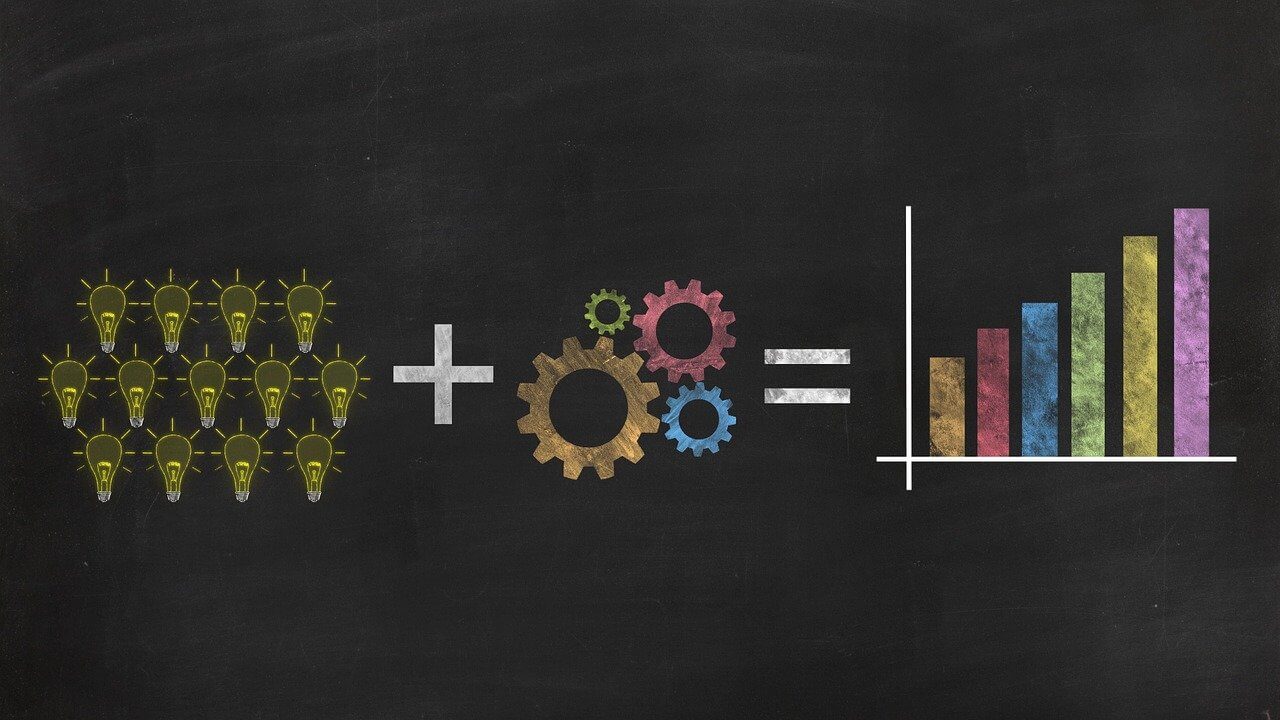

Recent Breakthrough in Development: Systems Thinking One of the recent breakthroughs in organizational and management…

What Is an Organic Approach? Organization and management sciences today are placing a great deal…