I hope to get a least a smile from my film metaphors, but what do you expect from an actor turned trainer? When we write it is said we should always write what we know. And, that is what I have tried to do here. I hope you find my take interesting or entertaining (hopefully both), but, most of all, in caveman speak, that I bring food for the cave. Food for thought, nourishment for the soul, vitamins for energy, etc.

I find training and development to be a fascinating field although my approach may sometimes deviate a bit to the employee or trainee side of things rather than the trainer, training developer, or training manager. These days, at a time when we really need to see the people in the jobs perform their best, and knowing the uncertainty of the economy, trainers need to do what seems impossible and see that it gets done.

And we have to do it with fewer resources than we used to have, meaning more in-house training, less outsourcing–if at all, and do more than just train. We need to give hope, motivate and or train. We need to see the “good, the bad, and the ugly” of training, and make any training the “affair to remember” of my last article. Understand when I say the “ugly” of training, I only mean the process our trainees may find utterly boring and repulsive. We can’t help that on the surface so much–the fact it exists or we must train on certain subjects that in themselves are boring and perceived by some as a waste of time. That subject training may be mandated by law.

But we can try to make the most of it by reaching out to those who find it repugnant to see value in it–like it or not–out of necessity. That means dealing with individuals to whom the subject or the process seems entirely unnecessary. This means acknowledging at a minimum there is more to people than their job. We can’t ignore their job and their place in the company; however, we can try to incorporate it within their reality of survival–their world being more than company.

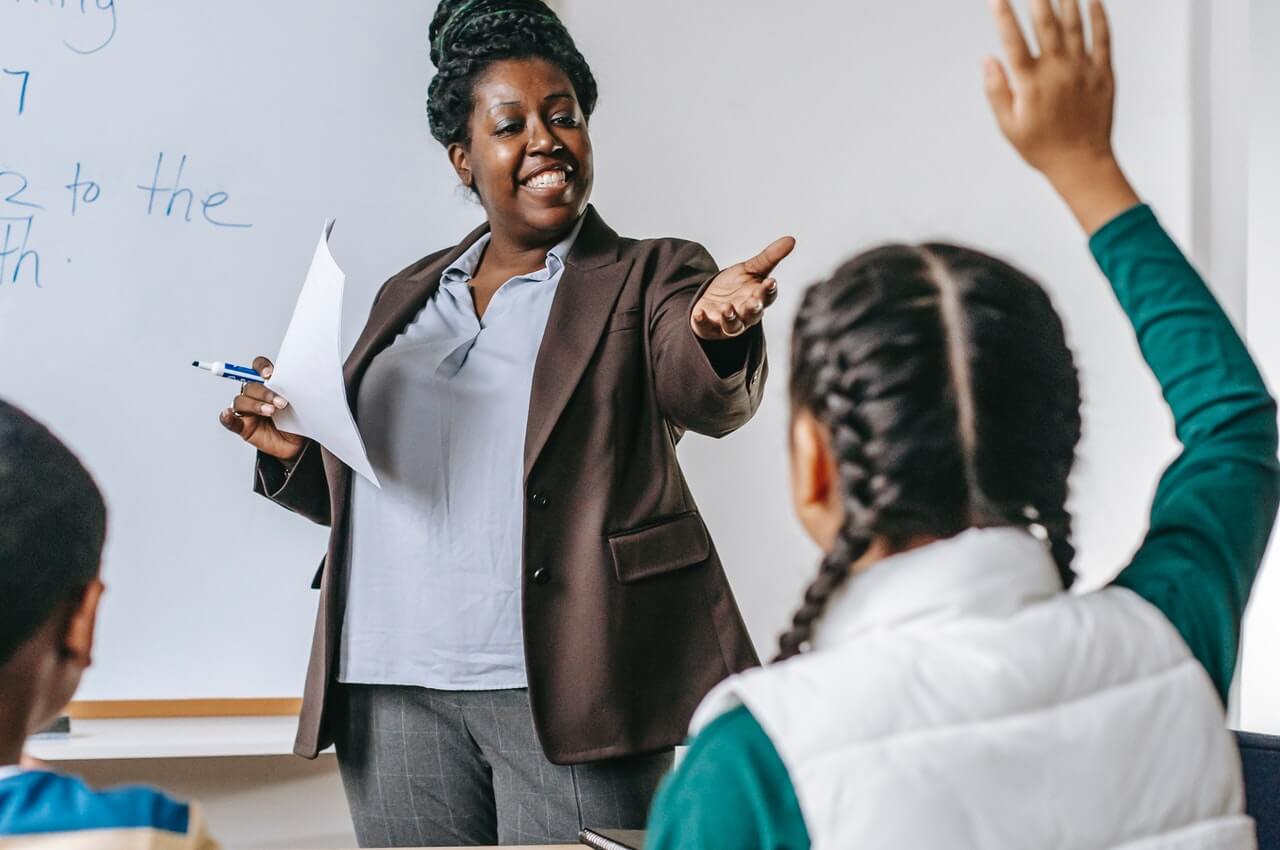

Some see their jobs only as a means to survive; however, I think most of us enjoy our jobs–or at least try to make the best of them. Sometimes those jobs become us and who we are–our very identity. Remember, Death of a Salesman, a perfect tragedy of a life ruined by becoming too much of one thing and forgetting the rest of his identity is important, too. This has been said often by teachers and trainers, and you’ve said it yourself, we shouldn’t train subjects but people. Ironic isn’t that in some countries subjects and people can be the same thing. We no longer have a monarchy ruling this country so people aren’t subjects. While people learn subjects, they really have to be connected or should be, dare I say it, to Maslov’s Hierarchy of Needs. We should identify people as being more than the job. The subjects we train or teach are a part of the whole–not the whole.

When I wrote What Would A Caveman DO: How We Know What We Do About Training, I was writing about a simplified time, when training was a matter of survival, when people needed and wanted to learn more to do their jobs more efficiently. Doing their jobs more efficiently put more food on the table, made a better shelter, or otherwise helped them survive and thrive.

We have to have a similar take on training even today. If we can’t directly help someone survive this economy, we can at least acknowledge trainees as people who have the same worries as the rest of us, and make it positive. The off-hand remark a trainer may make about having to take a break because it’s in the curriculum or labor union rules, “and we have much more to cover” doesn’t help to promote the feeling we are all in this together.

This is not the time to joke about real lives. People need a break to breathe, to stretch their legs, and to use the bathroom, but also to put things in perspective, to call home and check on the sick kid, to connect with the wife to see if she needs anything–personal stuff. Those things that make them people–human beings.

I’m not saying we aren’t doing these things. Most of us probably are, but I am saying they are still important to do. Everyone wins. To make people a part of the equation means we are the “good;” to not do so, the “bad;” and we know the “ugly” training exists no matter what. Dealing with it positively makes the experience worthwhile for all–even the trainers. No one should feel they are not being served by training. Know that we are all happier doing our job when it is more pleasant. When people appreciate us, we like it. It increases our self esteem.

As trainers, we have the best jobs in the world because we have to be so multifaceted as human beings; the trick is in using these facets together in training others. We trainers must be psychologists, teachers, counselors, trainers, philosophers, and oftentimes, subject-matter-experts as well. It wouldn’t hurt us to do our best to be people experts. In fact, it wouldn’t hurt at all. It might even do a lot of good. I hope you agree.

This has been my take on the “good, the bad, and the ugly” of training. I hope I brought food to the cave and something to think about. I look forward to hearing from you–either here in comment form, or via e-mail. Or, if you like, check out my website. I’m always open to questions and suggestions of topics. If I don’t have a good answer your question or can adequately write about your suggestion in a short article, I’ll try to find someone who feels they can. Maybe that’s you. Let me know. I want to know what you think.

—

For more resources about training, see the Training library.

By the way, my new eBook is available through most major distributors and in most formats. The Cave Man Guide to Training and Development is a look at training through the eyes of others, taking the notion to another more basic level to explore ways we can simplify what we do. We spend so much time “branding” ourselves so we have a different approach to sell. Maybe what we have has complicated the picture for the very people we want to sell to. I have written a book to help us re-think what we do and ask some questions of why. Who is to say, this won’t work for your brand of training; it may even help.