Project Management

Most Popular

In the last two decades, software development has undergone an Agile transformation because of the many benefits like improved quality and predictability across projects. Agile methods have become the standard in many contexts, using small, self-directed teams to create a product in short order. In this article, we’re going to cover the basics of the …

In some ways, the history of project management is the history of the 20th century. It begins with Henry Gantt inventing his handy chart and continues through many of the most significant events in modern history. World wars, space shots, and the Internet all depended in some way on the development of project management. Today, …

One of the most important books in the project manager’s library is the Project Management Book of Knowledge. It contains processes that smooth any aspect of a project, grouped into five process groups or project management phases. While they don’t contain a specific method of organizing a project, they can be used with any sort …

All About Project Management Test – How Good Are Your Own Project Management Skills? Sections of This Topic Include Foundations of Project Management What is Project Management? Overviews of Project Management Basics of Project Planning Roles in Project Management (including Project Manager) Skills Required to Leading Teams and People in Project Management Project Planning Feasibility …

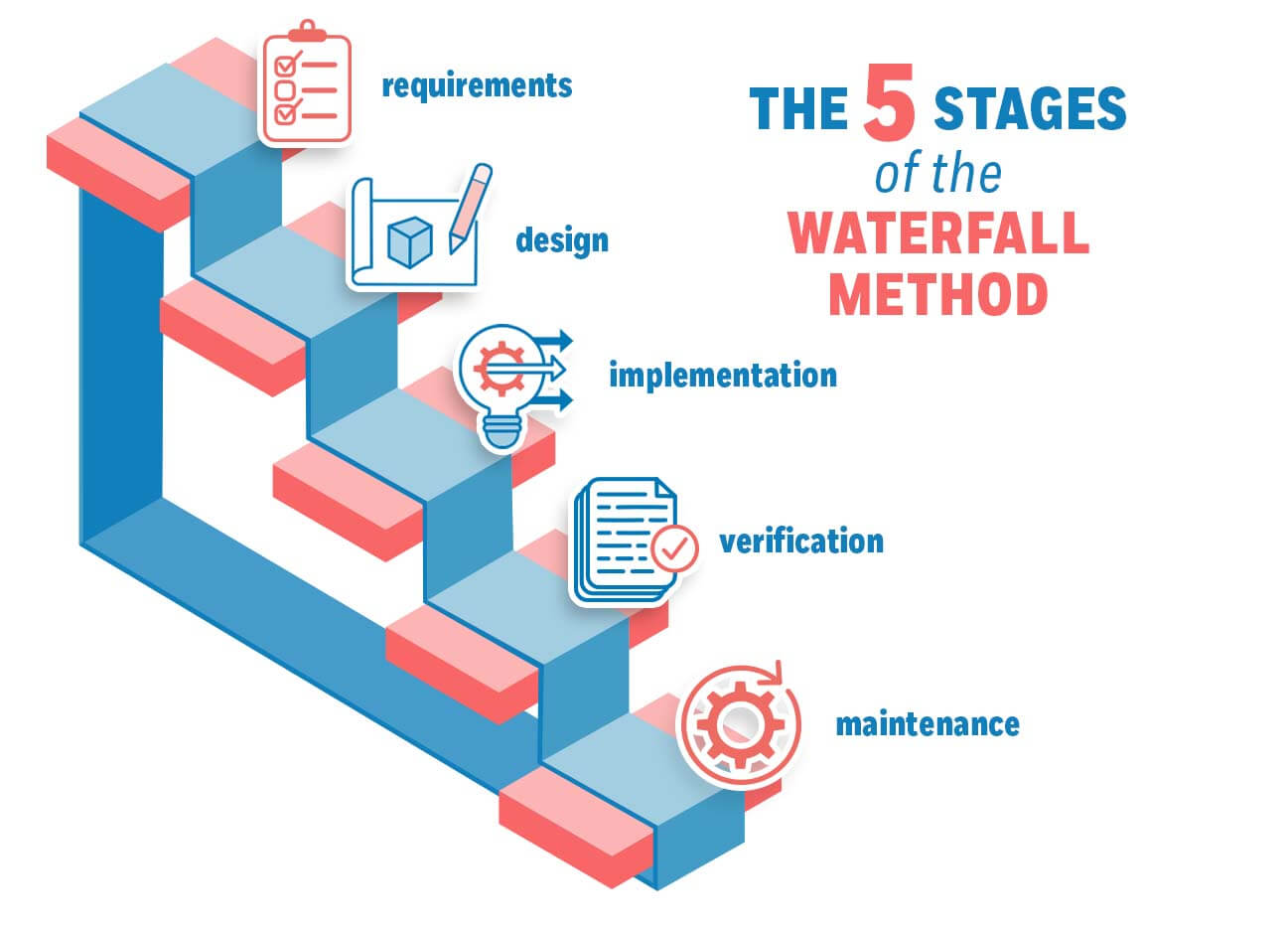

If you’re discovering potential project management methodologies for a new project, you might’ve come across a lot of project management jargon. If you aren’t already familiar with them, terms like the waterfall, scrum, agile, lean, and kanban methodologies aren’t immediately digestible. This guide is all about explaining one of these terms: the waterfall methodology, also …

Every year, project management conferences come with a promise of learning and networking opportunities for project management professionals. The good news is that this year is no exception. If you have been looking forward to the next big event, here is a comprehensive list of the top project management conferences in 2023. Interest in Project …

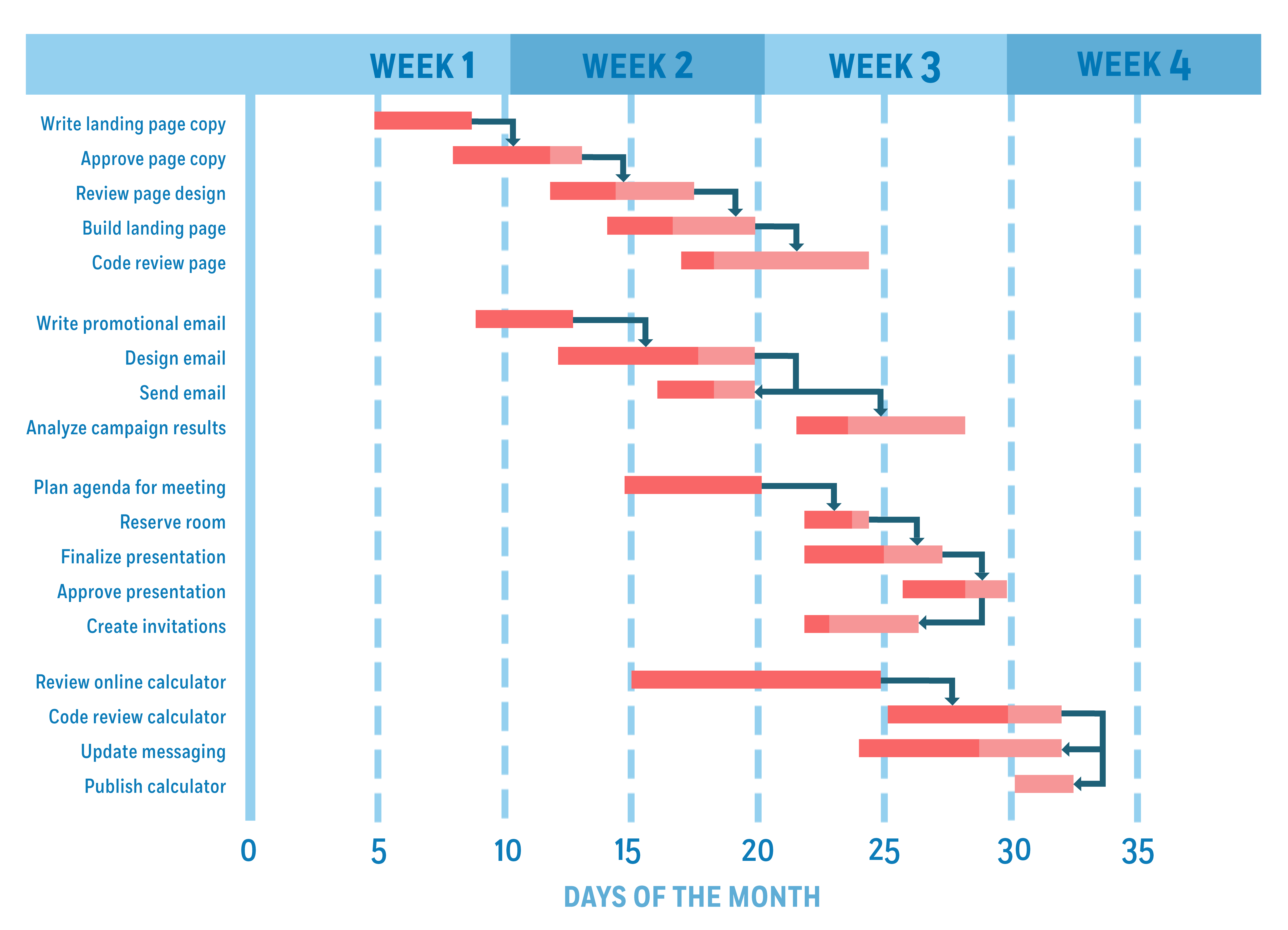

Gantt charts are a popular and time-tested way of visualizing project workflows. But they’re not just for any project. This project visualization approach aligns with the waterfall methodology that focuses on completing a task or process before the next one can begin. A Gantt chart lets you organize a project’s timescale and create an overview …

The issue of scope creep has bedeviled project managers since the ancient Egyptians wondered if three pyramids might be more impressive than just one. It isn’t a difficult concept to understand. However, heading off scope creep often requires a great deal of effort and expertise. Key Takeaways: Scope Creep Project scope is the project’s goal …

Gantt charts are a popular and time-tested way of visualizing project workflows. But they’re not just for any project. This project visualization approach aligns with the waterfall methodology that focuses on completing a task or process before the next one can begin. A Gantt chart lets you organize a project’s timescale and create an overview …

Scope creep is one of the biggest culprits for delayed large projects. A lack of clear requirements, involving the wrong stakeholders, lack of documented functional and non-functional requirements, and poorly defined map process flows all contribute to scope creep. Luckily, there are many strategies a project manager and all project stakeholders can put in place …

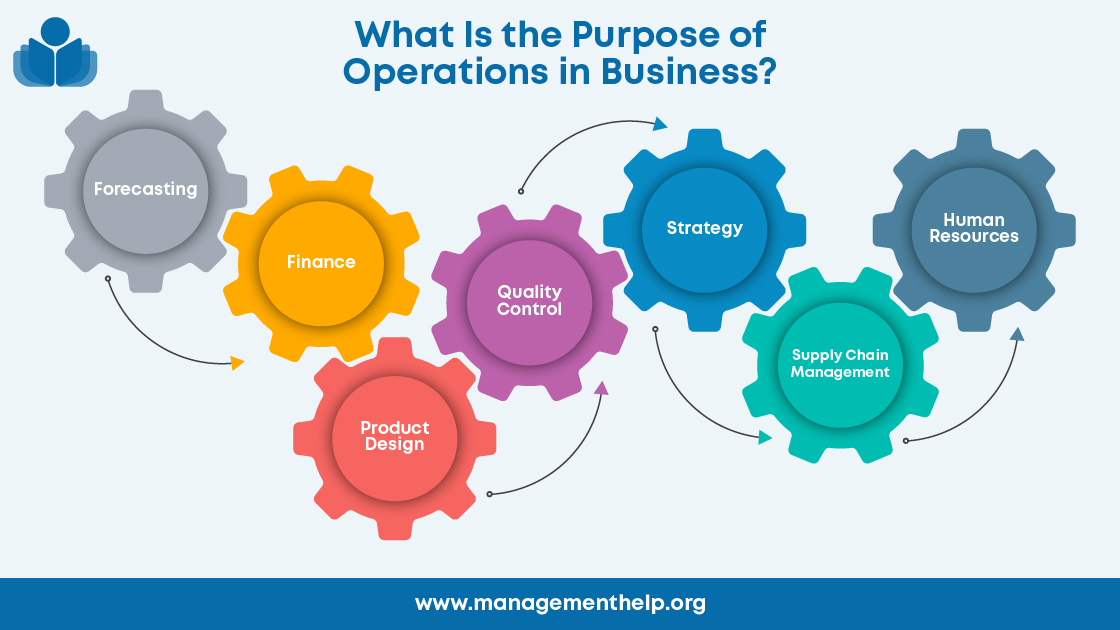

Business operations is an elusive but necessary part of any organization looking to maximize productivity and profit potential. Companies that struggle to understand operational demands often miss key opportunities to succeed. This article explains how operations applies to businesses and tips for improving efficiency across the board. What Are Operations in a Business? An operations …

KEEPING THE WOLVES AT BAY — The Ever-Present Conundrum The recent events in the financial sector, while perhaps skirting the edges of legality, certainly highlighted the issue of the ethical dilemma often faced when increasing pressure to perform, deliver and maximize profitability butts up against moral and ethical (as well as legal) compliance. Certainly in …

People operations empower your employees to become productive and fulfilled in the workplace. It’s essential for you to invest time and effort in people ops because your workforce is the backbone of your business. Although the term “people operations” is relatively new, it’s a traditional concept that is closely related to human resources (HR). What …

If you’re an American reader of this blog and you’re involved in, or interested in, project management, then you’re probably familiar, or at least heard of A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). In this article I want to introduce you to a complimentary approach to project management which was developed …

Anyone who has been responsible for a work schedule knows how complicated they can be. Imagine how much more complicated the schedule for producing an app or even constructing a building must be. Project scheduling is an involved topic that can be bewildering. However, those who take the time to understand it will discover a …

I have been having an ongoing discussion with a global company that has been having big issues in delivering its major customer projects. They are looking to develop a strategy for provision of real project managers / and or professional project management expertise to help. In doing this, they are having an important debate: Should …

In the last two decades, software development has undergone an Agile transformation because of the many benefits like improved quality and predictability across projects. Agile methods have become the standard in many contexts, using small, self-directed teams to create a product in short order. In this article, we’re going to cover the basics of the …

One of the most important books in the project manager’s library is the Project Management Book of Knowledge. It contains processes that smooth any aspect of a project, grouped into five process groups or project management phases. While they don’t contain a specific method of organizing a project, they can be used with any sort …

If you’re discovering potential project management methodologies for a new project, you might’ve come across a lot of project management jargon. If you aren’t already familiar with them, terms like the waterfall, scrum, agile, lean, and kanban methodologies aren’t immediately digestible. This guide is all about explaining one of these terms: the waterfall methodology, also …

The issue of scope creep has bedeviled project managers since the ancient Egyptians wondered if three pyramids might be more impressive than just one. It isn’t a difficult concept to understand. However, heading off scope creep often requires a great deal of effort and expertise. Key Takeaways: Scope Creep Project scope is the project’s goal …

There is no single agreed-upon definition of project management methodologies. However, in broad strokes, it can be thought of as a set of guidelines, principles, and processes for meeting or exceeding a project’s requirements. Any project management methodology may help you complete a project. That’s not quite the same thing as saying any methodology will …

Agile project management (APM) is a project philosophy that breaks projects down into iterations or sprints. The purpose is to produce bigger ROI, regular interactions with clients and end-users, and improved delivery of product features. Today, Agile is used in virtually every industry from software development to real estate. Keep reading to learn more about …

Every project comes with its unique challenges. But there’s one challenge that accompanies every project you’ll work on: deciding which project management methodology to choose. The waterfall vs agile question is the most frequent one you’ll come across in this discourse. As important as it is to answer, this question might have you bogged down …

A few weeks ago I was assisting a project manager with a troubled project. We reviewed the documentation from the beginning, starting with the usual suspects: project charter, WBS, schedule. They all seemed fairly straightforward and understandable. Once we got to his status reporting though, confusion started. This project’s status reports were spreadsheets about 10 …

Project management software for consultants empowers you to supervise client projects efficiently. Plus, it makes it simple for you to collaborate with team members and evaluate project results. Find out which best project management software for consulting firms is the right choice for you. Best Project Management Software for Consultants Methodology for Project Management Software …

Managing projects isn’t getting any easier. Thanks to a global pandemic, many businesses now allow workers to work from home full-time. The right project management software may be the only way to keep everything organized and moving in the same direction while having a grasp on how far along your team is on each project. …

The world of project management is forever changing. From new software to resource planning to technological development, keeping up to date with relevant blogs and resources is critical. We’ve listed some of the best blogs for staying aware of ideas and updates in the industry. Find your new favorite project management blog below. Interested in the …

In businesses large or small, it can be difficult to stay on top of everything that’s going on. Having a firm understanding of productivity and budgeting can spell the difference between success and failure. The best project management software with time tracking offers more than just time tracking in real time. Automating time tracking can …

Project managers often struggle to find the one software that will fill their needs. It’s not uncommon for team leaders to try out one software, only to migrate to another one. In this Confluence review, we analyze the project management software so you can find out if it’s the right fit for your team. Our …

Microsoft has been supplying business software for decades, and its weight of experience is hard to overcome. Wrike is one of the best of the new approaches: project management as work management. Microsoft Project offers a robust toolset, but in a battle between Microsoft vs Wrike, it’s Wrike that could be a better choice for …

A Gantt chart is a project management tool used to visualize a project plan. It’s a useful way of showing scheduled tasks and task due dates. Gantt charts help team members and project managers view the start dates, end dates, and milestones of a project in one simple stacked bar chart. What is a Gantt …

If you’re running a small business and need help managing your team and projects, free project management software can help you dramatically. Manually managing your projects is both headache-inducing and highly inefficient. Luckily, there are plenty of options for free project management apps. Best Free Project Management Software Methodology for the Best 6 Free Project …

More in Project Management

When I started my working life, at IBM, years went by before I had any sub-contractors as part of my project team. We could handle just about every request with in-house skills. Alas, almost 20 years later those days are gone, and the opposite has become the norm. It is nigh on impossible to deploy …

The following is a guest post by Susan Shearouse, author of Conflict 101. Early morning, the mists rising off the placid river, the crew racing in that long sleek boat, each team member pulling through the strokes in unison, the team leader sitting at the back calling commands. Ahhh, teamwork… What happens when the reality …

In this blog we talk mostly about project managers and how they can steer the project towards success: how they can start with a strong business justification, do robust planning, enact good change control. But there is another player in the project’s cast of characters who is just as important, if not more, than the …

As a general rule, project teams will agree with the idea that Risk Analysis makes for a better project. It gives the team visibility of worrisome items, a forum to prioritize them, and some time to react before the risk materializes. So why don’t more project managers incorporate Risk Analysis regularly in their project’s governance? …

All organisations that have existed for at least some time will have developed a “culture”. In its most simplest, it is the values and habits that are promoted by the organisation is being important, or even crucial to the business. This could be and often is extended to the behaviours that individuals and even teams’ exhibit in discharging normal business – and this can and will include projects.

There will be milestones in our projects –or initiatives- that are important because they determine what the project team does next. Maybe it’s a ‘Scope Definition’; maybe it’s a ‘Design Review’. When these important decisions surface, sometimes project teams tend to swell – even though you, the Project Manager, have not asked for more resources. …

Supporters of project management templates will try to tell you this is the only way to ensure best practices are embedded in project planning. While templates provide some form of guidelines that ensures information completeness, they have their limitations and drawbacks.