Starting a Business

Most Popular

Rental properties are a great way to earn income either full-time or on the side. However, some states are better than others regarding returns on these types of investments. This article looks at the 10 best states to buy investment property this year (and the worst states for real estate). 1. South Carolina One of …

Guest post from Jack Hoban. What are Values? According to the dictionary, values are “things that have an intrinsic worth in usefulness or importance to the possessor,” or “principles, standards, or qualities considered worthwhile or desirable.” However, it is important to note that, although we may tend to think of a value as something good, …

Many people are used to reading or hearing of the moral benefits of attention to business ethics. However, there are other types of benefits, as well. The following list describes various types of benefits from managing ethics in the workplace. 1. Attention to business ethics has substantially improved society. A matter of decades ago, children …

All About Business Planning: Complete Manual With Updated Extensive Resources Copyright Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD. NOTE: Your business plan should be highly customized to your current organizational situation. Thus, using a generic business plan template could completely misrepresent the needed focus of your business plan. (This step-by-step manual is a complement to the topic How …

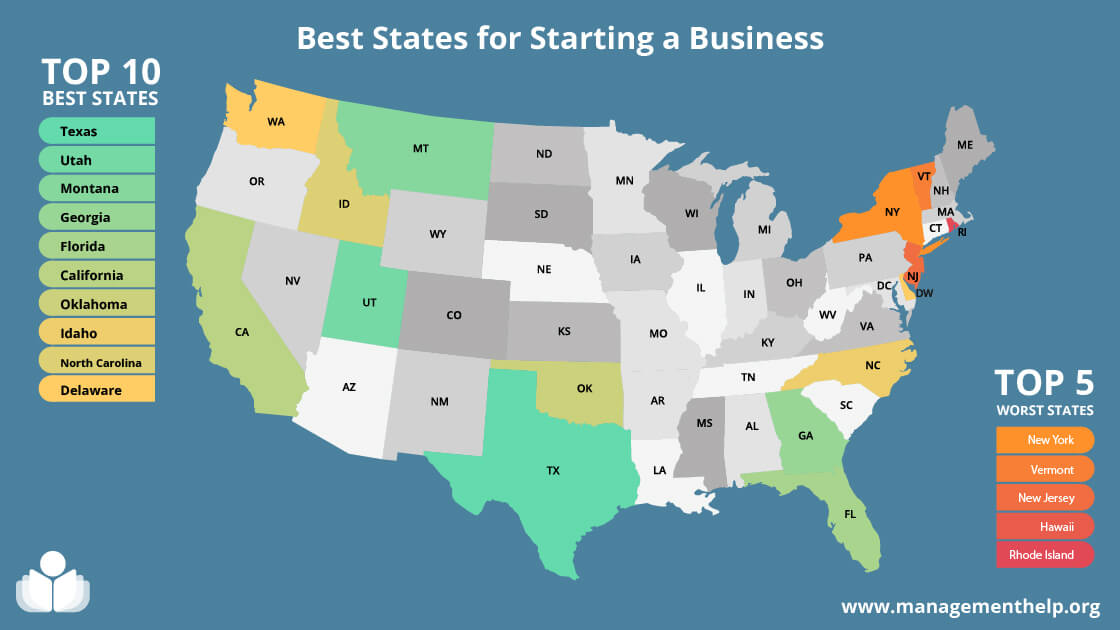

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, around 47 million people quit their jobs in 2021. Then, roughly 5.4 million new business applications were filed, a 53% increase from 2019. If you’re thinking about joining this entrepreneurial club, several crucial decisions lie ahead. Below are the best states for starting your business. The Best …

Inc Authority makes it possible for you to set up a limited liability company (LLC) for free. It simplifies the business registration process through its extensive LLC formation services, excellent customer support, and affordability. In this Inc Authority review, we cover its pros, cons, pricing, and features. Find out if the Inc Authority LLC service …

Business ethics in the workplace is about prioritizing moral values for the workplace and ensuring behaviors are aligned with those values — it’s values management. Yet, myths abound about business ethics. Some of these myths arise from general confusion about the notion of ethics. Other myths arise from narrow or simplistic views of ethical dilemmas. …

The process of forming a corporation or LLC (Limited Liability Company) can be complex and time-intensive. Fortunately, an online business formation service like ZenBusiness can make the process easier. In this ZenBusiness review, you’ll learn what else it offers beyond easy-to-use LLC services and competitive pricing. Our Verdict ZenBusiness at a Glance ZenBusiness has a …

Rental properties are a great way to earn income either full-time or on the side. However, some states are better than others regarding returns on these types of investments. This article looks at the 10 best states to buy investment property this year (and the worst states for real estate). 1. South Carolina One of …

Are you looking for the best type of business to quickly start your own company and finally ditch your traditional 9-to-5 job? The market is growing and expanding due to changing trends, so if you have the ambition to start a new business in 2023, we’ve wrapped up the five types of business that will …

Guest post from Jack Hoban. What are Values? According to the dictionary, values are “things that have an intrinsic worth in usefulness or importance to the possessor,” or “principles, standards, or qualities considered worthwhile or desirable.” However, it is important to note that, although we may tend to think of a value as something good, …

Many people are used to reading or hearing of the moral benefits of attention to business ethics. However, there are other types of benefits, as well. The following list describes various types of benefits from managing ethics in the workplace. 1. Attention to business ethics has substantially improved society. A matter of decades ago, children …

Business ethics in the workplace is about prioritizing moral values for the workplace and ensuring behaviors are aligned with those values — it’s values management. Yet, myths abound about business ethics. Some of these myths arise from general confusion about the notion of ethics. Other myths arise from narrow or simplistic views of ethical dilemmas. …

The following guidelines ensure the ethics management program is operated in a meaningful fashion: 1. Recognize that managing ethics is a process. Ethics is a matter of values and associated behaviors. Values are discerned through the process of ongoing reflection. Therefore, ethics programs may seem more process-oriented than most management practices. Managers tend to be …

It’s ironic that a word like “transparency” can have several confusing meanings, even in a business context. While transparency as a concept is often most visible in the realm of social responsibility and compliance, its real benefit is when it’s seen as a business priority. Transparency is about information. It is about the ability of …

What’s an Ethics Management Program? Organizations can manage ethics in their workplaces by establishing an ethics management program. Brian Schrag, Executive Secretary of the Association for Practical and Professional Ethics, clarifies. “Typically, ethics programs convey corporate values, often using codes and policies to guide decisions and behavior, and can include extensive training and evaluating, depending …

Let’s Start With “What is ethics?” Simply put, ethics involves learning what is right or wrong, and then doing the right thing — but “the right thing” is not nearly as straightforward as conveyed in a great deal of business ethics literature. Most ethical dilemmas in the workplace are not simply a matter of “Should …

As opposed to offering opinions without having all of the background and knowledge, I thought it might be more helpful to start a discussion about the questions: Many people have written that Toyota’s problem was that it sacrificed a core value of safety for profit. To frame the issue this generally is to miss the …

Inc Authority makes it possible for you to set up a limited liability company (LLC) for free. It simplifies the business registration process through its extensive LLC formation services, excellent customer support, and affordability. In this Inc Authority review, we cover its pros, cons, pricing, and features. Find out if the Inc Authority LLC service …

The process of forming a corporation or LLC (Limited Liability Company) can be complex and time-intensive. Fortunately, an online business formation service like ZenBusiness can make the process easier. In this ZenBusiness review, you’ll learn what else it offers beyond easy-to-use LLC services and competitive pricing. Our Verdict ZenBusiness at a Glance ZenBusiness has a …

Registering your own business doesn’t have to be daunting. Business registration services exist to streamline the process from start to finish while keeping everything compliant down the road. The best business registration services can file business formation documents for you, provide registered agents, and prepare your annual reports. Best Business Registration Services ZenBusiness – Best …

The LLC formation process can be complicated and time-intensive, especially if you are unsure about the regulations and laws that apply. This MyCompanyWorks review shows how the LLC service simplifies and speeds up this process. It’s a good choice for aspiring entrepreneurs who want to dodge the hassle of dealing with tons of legal paperwork. …

Whether you’re starting a new business or converting an existing company to a limited liability company (LLC), the best LLC services can make it easy to do. Typically, LLC business formation services offer assistance with paperwork, filing, and registered agent services. We’ve gathered the top online LLC services according to what we think they do …

As the name suggests, Northwest Registered Agent at its core is a registered agent service, but in this review of Northwest Registered Agent you’ll see it offers a lot more. If you want to start an LLC, having a registered agent is a must to handle government, tax, and legal matters on your behalf. You …

After registering your business as an LLC, you have one more crucial decision to make. It’s whether you want to set up your management structure as a member-managed LLC vs manager-managed LLC. A member-managed LLC means the owners have combined control over business decisions. On the other hand, a manager-managed LLC assigns one or more …

A Limited Liability Company is a great business structure to consider, no matter what type of business you plan to run. The many benefits of an LLC allow business owners to build the company they desire while minimizing hardships along the way. This article explains the LLC advantages and disadvantages you’ll want to know about …

All About Business Planning: Complete Manual With Updated Extensive Resources Copyright Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD. NOTE: Your business plan should be highly customized to your current organizational situation. Thus, using a generic business plan template could completely misrepresent the needed focus of your business plan. (This step-by-step manual is a complement to the topic How …

Developing strategy takes time and resources. It requires the time and commitment of some of the most highly paid and highly experienced people in your organization. So, if your team isn’t willing to invest what is needed, I recommend that you don’t do it. Poor planning is often worse than no planning at all. So, …

Legal Structures of Organizations Legal Forms and Traditional Structures of Organizations Market Research — Inbound Marketing Planning Your Research Market Research Find and Feed the Feeling Strategizing Understanding Strategy and Strategic Thinking Competitor Analysis Porter’s Five Competitive Forces (Part I) Porter’s Five Competitive Forces (Part 2) Competitive Intelligence Product Planning Product Management E-Commerce Sales and …

As the strategy leader, you have seven activities to which I recommend you pay close attention to build a strong strategy that has full buy-in and commitment. Gain your team’s commitment and buy-in to the process If your leadership team members are like most with whom I have worked, they are stretched for resources and …

The historian Alfred Chandler of Harvard Business School wrote a seminal book published in 1977 on the history of strategic decision making at the highest levels of Corporate America , including DuPont, General Motors, Standard Oil and Sears Roebuck. The book was called The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. In this work …

There is often a great deal of confusion about the difference between business plans and strategic plans. And, frankly, they are similar in many ways, and since each plan has to be tailored to the organization it is prepared for, one can easily blur into the other. In both cases, you begin with internal and …

The principles of strategy are timeless. The following notes on the essentials of strategy are drawn from the great works of strategy… Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Napoleon’s Maxims, Clausewitz’ On War. Though dating up to 2,500 years ago, the advice of these strategists is helpful today no matter your competitive landscape, from high …

Good Strategy Bad Strategy This fresh approach to strategic thinking begins with tales of battles at sea in the days of Napoleon and continues to explain what kinds of strategies have made the difference for modern companies like Apple, Wal-Mart, Cisco, Starbucks and Wells Fargo. Author Richard Rumelt shows that many recent high profile failures …

More in Starting a Business

Many startup businesses set up incentive or commission-based compensation systems for their initial employees. This is often done because they can’t afford to pay staff what they’re worth. As an enticement they offer the opportunity to earn much more than a smallish base salary if these early staff achieve great success. This is common in …

Lately I’ve been rethinking business plans. On the one hand, in the consulting and academic world, what is meant by a business plan is a fairly comprehensive research project with thorough analysis of issues including customers, markets, competitors, pricing, marketing strategies, risks – always followed with detailed multi-paged financial projections looking three to five years …

The role of the board changes as the company grows and the management team becomes more diverse, with a wide range of experts who can contribute to strategy in different ways. A company passes through several stages in its life cycle. In the first stage ‘Start-up’ strategy is developed and implemented by the founder and …

If you only looked at the headlines of today’s feature in the Wall Street Journal: The Case Against Social Responsibility, you might think that the ire of business ethics professionals would be raised to the level of hysterics. But Professor Aneel Karnani raises a critical point that is at the heart of not only corporate …

Every business should do at least SOME business planning before starting or expanding operations. Whether that’s the two page version with targets, the five page variant with some analysis (more on that next week), or the 37 page detailed masterpiece, every business needs to do some of this. There are two basic steps to business …

From the days of ancient warfare, large armies have struggled with an inherent disadvantage: Sheer size presents an easy target for a quick and nimble attack force. The red-coated, regimented British struggled to fend off undisciplined American revolutionaries. The Vietnam era Americans could not defend themselves adequately from the pesky, unpredictable Viet Cong. In the …

It has often been said that there is no place in the boardroom for a director who does not understand the business. Now we need to consider if there is room for one who does not understand internet enabled connectivity. Directors need to understand both the risks and the opportunities presented by the internet in …