Interested in learning about the importance of registering a DBA in Wyoming and how to go about it? You’re in the right place. A DBA, meaning “doing business as,” lets Wyoming entrepreneurs operate under a different name for marketing, sales, and legal purposes. In other states, it’s sometimes called a fictitious, assumed, or trade name. …

Starting a Business

Most Popular

Are you an entrepreneur seeking valuable insights, inspiration, and strategic ideas from industry experts? Look no further! We have compiled a list of the 32 best business podcasts to help you stay up-to-date with the latest trends, learn from successful entrepreneurs, and grow your business. Whether you’re a startup founder, a small business owner, or …

Guest post from Jack Hoban. What are Values? According to the dictionary, values are “things that have an intrinsic worth in usefulness or importance to the possessor,” or “principles, standards, or qualities considered worthwhile or desirable.” However, it is important to note that, although we may tend to think of a value as something good, …

Many people are used to reading or hearing of the moral benefits of attention to business ethics. However, there are other types of benefits, as well. The following list describes various types of benefits from managing ethics in the workplace. 1. Attention to business ethics has substantially improved society. A matter of decades ago, children …

Rental properties are a great way to earn income either full-time or on the side. However, some states are better than others regarding returns on these types of investments. This article looks at the 10 best states to buy investment property this year (and the worst states for real estate). 1. South Carolina One of …

Business ethics in the workplace is about prioritizing moral values for the workplace and ensuring behaviors are aligned with those values — it’s values management. Yet, myths abound about business ethics. Some of these myths arise from general confusion about the notion of ethics. Other myths arise from narrow or simplistic views of ethical dilemmas. …

How One Typical Facilitator (Mistakenly) Concluded the Client Wasn’t Doing Strategic Planning I got a call last week from a facilitator, asking for advice about an aspect of strategic planning. He kept asserting that his client, a manufacturer of outdoor recreational equipment, wasn’t doing strategic planning. I asked how he came to that conclusion. He …

Developing strategy takes time and resources. It requires the time and commitment of some of the most highly paid and highly experienced people in your organization. So, if your team isn’t willing to invest what is needed, I recommend that you don’t do it. Poor planning is often worse than no planning at all. So, …

Complete Business Planning Guide with Extensive Resources Copyright Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD. NOTE: Your business plan should be highly customized to your current organizational situation. Thus, using a generic business plan template could completely misrepresent the needed focus of your business plan. (This step-by-step manual is a complement to the topic How to Start Your …

Accredited Debt Relief stands out as a beacon of hope for those struggling with debt in the vast landscape of financial solutions. With many options competing for your attention, the key question is whether Accredited Debt Relief is the guiding star of legitimacy leading you toward financial freedom, or just another fleeting light in the …

How much will it cost to start your business? Anyone thinking about becoming an entrepreneur needs to ask this key question. You must take time to figure out your startup costs. This helps you know how much money you need to raise and if starting your business makes sense. It’s great to determine how much …

In the complex world of debt relief, where promises can often seem too good to be true, one pressing question remains: Is Freedom Debt Relief the real deal or just another financial mirage? This company has gained attention for its commitment to helping individuals escape debt through negotiations with creditors. Yet, opinions are divided. Some …

If you’re having difficulty managing your debt and facing the possibility of default, a debt relief company might help. Debt relief can take various forms, including options you can pursue on your own, but a debt relief company can guide you through the process. Keep in mind, though, that their services come with a fee. …

Navigating the complexities of financial debt can often feel overwhelming, leading many to wonder: Is National Debt Relief legitimate? This is a common concern for those seeking a way out of financial distress. In this exploration, we will examine the legitimacy and effectiveness of National Debt Relief to determine whether it truly offers a path …

Are you an entrepreneur seeking valuable insights, inspiration, and strategic ideas from industry experts? Look no further! We have compiled a list of the 32 best business podcasts to help you stay up-to-date with the latest trends, learn from successful entrepreneurs, and grow your business. Whether you’re a startup founder, a small business owner, or …

Rental properties are a great way to earn income either full-time or on the side. However, some states are better than others regarding returns on these types of investments. This article looks at the 10 best states to buy investment property this year (and the worst states for real estate). 1. South Carolina One of …

The world is changing at an unprecedented pace. The advent of new technologies, the rise of the digital economy, and the changing needs of consumers have all contributed to a shift in the business landscape. Entrepreneurs continuously look for innovative, profitable, and profitable business ideas. This guide will explore the 131 best businesses to start …

In the ever-evolving world of entrepreneurship, operating under a fictitious business name, or “Doing Business As” (DBA), can be a smart strategic move. Whether a solo entrepreneur or managing a small business, a DBA allows you to brand your enterprise distinctively. This guide will unravel the intricacies of filing a DBA, equipping you with the …

Are you looking for the best type of business to quickly start your own company and finally ditch your traditional 9-to-5 job? The market is growing and expanding due to changing trends, so if you have the ambition to start a new business in 2023, we’ve wrapped up the five types of business that will …

Choosing a name for your LLC can be tricky. Ensuring the name reflects your business’s products or services is essential. However, several other factors must be considered when selecting an LLC name. First, you need to follow specific rules for naming your LLC. These rules and requirements vary depending on the state where your business …

Something as small as a business name can have a monumental impact on your success. The right name can bring in more customers than you thought possible, whereas the wrong name can effectively shut you down. Read on to discover how to come up with a business name that sets you apart from the competition. …

In the fast-paced and ever-evolving business world, staying informed about the latest trends, insights, and strategies is crucial for entrepreneurs, executives, and professionals. While numerous sources of information are available, business newsletters have emerged as a popular and convenient way to receive curated content directly in your inbox. These newsletters provide valuable knowledge and save …

Guest post from Jack Hoban. What are Values? According to the dictionary, values are “things that have an intrinsic worth in usefulness or importance to the possessor,” or “principles, standards, or qualities considered worthwhile or desirable.” However, it is important to note that, although we may tend to think of a value as something good, …

Many people are used to reading or hearing of the moral benefits of attention to business ethics. However, there are other types of benefits, as well. The following list describes various types of benefits from managing ethics in the workplace. 1. Attention to business ethics has substantially improved society. A matter of decades ago, children …

Business ethics in the workplace is about prioritizing moral values for the workplace and ensuring behaviors are aligned with those values — it’s values management. Yet, myths abound about business ethics. Some of these myths arise from general confusion about the notion of ethics. Other myths arise from narrow or simplistic views of ethical dilemmas. …

The following guidelines ensure the ethics management program is operated in a meaningful fashion: 1. Recognize that managing ethics is a process. Ethics is a matter of values and associated behaviors. Values are discerned through the process of ongoing reflection. Therefore, ethics programs may seem more process-oriented than most management practices. Managers tend to be …

It’s ironic that a word like “transparency” can have several confusing meanings, even in a business context. While transparency as a concept is often most visible in the realm of social responsibility and compliance, its real benefit is when it’s seen as a business priority. Transparency is about information. It is about the ability of …

What’s an Ethics Management Program? Organizations can manage ethics in their workplaces by establishing an ethics management program. Brian Schrag, Executive Secretary of the Association for Practical and Professional Ethics, clarifies. “Typically, ethics programs convey corporate values, often using codes and policies to guide decisions and behavior, and can include extensive training and evaluating, depending …

Do companies care about the intent of one’s actions, or just the results? While we think that our intentions should matter, if an unethical action takes place, do we really care why? Let me know what you would do in the following dilemma: Alternative #1 – You are taking care of a chatty 3-year old. …

As opposed to offering opinions without having all of the background and knowledge, I thought it might be more helpful to start a discussion about the questions: Many people have written that Toyota’s problem was that it sacrificed a core value of safety for profit. To frame the issue this generally is to miss the …

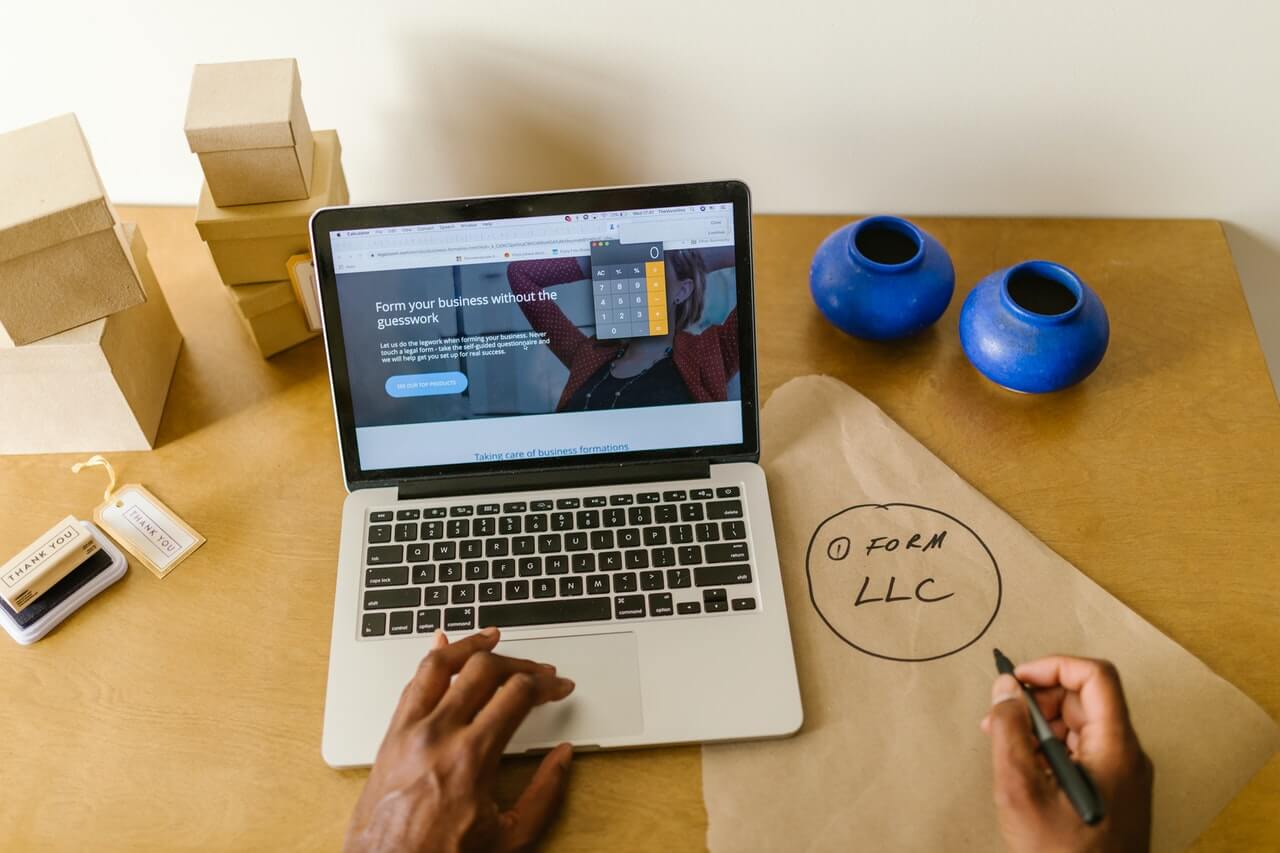

Imagine this: you’re about to launch your dream business, bursting with excitement and ready to make it happen. But then you hit a wall, the mountain of legal paperwork is more daunting than you expected, leaving you wondering where to start. That’s where LLC services swoop in like a superhero! By using online LLC services, …

Welcome to the thrilling universe of entrepreneurship! Here, dreams ignite, and ideas morph into reality. As a daring and visionary entrepreneur, you’re pumped to launch your next groundbreaking concept. Yet, before rocketing into the business world, there’s a vital step you can’t skip – registering your business with the right service provider. Wading through the …

Starting a business can be daunting, but the right support can make all the difference. That’s where MyCompanyWorks steps in, specializing in helping entrepreneurs form and manage their businesses. With so many options available, how do you know if MyCompanyWorks is the right choice for you? In this review, we’ll dive deep into the services, …

Are you searching for a reliable registered agent service to keep your business compliant and running smoothly? Look no further! In today’s fast-paced business world, choosing the right registered agent can make all the difference. That’s why we’ve deeply explored one of the industry’s top contenders, Northwest Registered Agent. This comprehensive review will explore Northwest …

Running a business means dealing with many documents, from contracts and invoices to tax forms and employee records. Keeping track of and managing these documents can be overwhelming. That’s where Bizee comes in, a document management platform designed to streamline your workflow and simplify managing your business documents. But is Bizee the right choice for …

Do you want to avoid the tangled and bewildering landscape of starting and maintaining a business? ZenBusiness might be your solution. In this review, we’ll explore this inventive platform to see how it aids entrepreneurs and small business owners in easily launching and growing their ventures. Whether you’re looking at forming an LLC, needing registered …

Are you ready to embark on the thrilling entrepreneurship journey but need help determining where to begin? Look no further! We’ve uncovered a hidden gem to help you navigate the world of business formation with ease. In this in-depth Inc Authority review, we’ll explore the ins and outs of this top-tier platform and reveal how …

Welcome to the fascinating realm of Limited Liability Companies (LLCs), where managing your business takes center stage. Imagine this: you’ve decided to embark on an entrepreneurial journey. Now, you face the crucial question of how your LLC should be managed. Should you go for a member-managed structure, where all owners actively participate in daily operations? …

How One Typical Facilitator (Mistakenly) Concluded the Client Wasn’t Doing Strategic Planning I got a call last week from a facilitator, asking for advice about an aspect of strategic planning. He kept asserting that his client, a manufacturer of outdoor recreational equipment, wasn’t doing strategic planning. I asked how he came to that conclusion. He …

Developing strategy takes time and resources. It requires the time and commitment of some of the most highly paid and highly experienced people in your organization. So, if your team isn’t willing to invest what is needed, I recommend that you don’t do it. Poor planning is often worse than no planning at all. So, …

Complete Business Planning Guide with Extensive Resources Copyright Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD. NOTE: Your business plan should be highly customized to your current organizational situation. Thus, using a generic business plan template could completely misrepresent the needed focus of your business plan. (This step-by-step manual is a complement to the topic How to Start Your …

The historian Alfred Chandler of Harvard Business School wrote a seminal book published in 1977 on the history of strategic decision making at the highest levels of Corporate America , including DuPont, General Motors, Standard Oil and Sears Roebuck. The book was called The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. In this work …

As the strategy leader, you have seven activities to which I recommend you pay close attention to build a strong strategy that has full buy-in and commitment. Gain your team’s commitment and buy-in to the process If your leadership team members are like most with whom I have worked, they are stretched for resources and …

In this post, we’ll discuss one of the most important phases in strategic planning – a phase that far too often is forgotten, resulting in plans that sit untouched on shelves. The plan for a plan should be developed by a Planning Committee and should answer 15 important questions — do this before the planners …

Far too often, organizations choose the wrong approach to strategic planning. As a result, strategic plans sit untouched on shelves and planners become even more cynical about goals-based or issues-based planning. This occurs especially with 1) new organizations, 2) organizations having many current issues, and 3) organizations having very limited resources. Here’s how to fix …

Legal Structures of Organizations Legal Forms and Traditional Structures of Organizations Market Research — Inbound Marketing Planning Your Research Market Research Find and Feed the Feeling Strategizing Understanding Strategy and Strategic Thinking Competitor Analysis Porter’s Five Competitive Forces (Part I) Porter’s Five Competitive Forces (Part 2) Competitive Intelligence Product Planning Product Management E-Commerce Sales and …

More in Starting a Business

If you’re interested in having a DBA in Nebraska and registering it, you’ve found the right place. A Nebraska DBA, or “Doing Business As,” lets entrepreneurs use a different business name for things like advertising, commerce, and legal matters. Some states may call this alternate name a fictitious name, assumed name, trade name, or similar …

If you want to learn about DBA in Pennsylvania, you’re in the right spot. In Pennsylvania, a DBA, also known as “doing business as,” lets individuals use a different business name for marketing, sales, and legal reasons. It can also be called a fictitious name, assumed name, or trade name, depending on where you are. …

If you want to understand why having a DBA in New York is important and how to register it, you’ve come to the right place. In New York, a DBA, also known as “Doing Business As,” lets business owners use a different name for things like marketing, sales, and legal matters. In some states, this …

Do you want to understand what DBA means in West Virginia and how to register? You’ve come to the right place. DBA, short for “doing business as,” lets individuals in West Virginia use a different business name for marketing, sales, and legal purposes. In some places, it might be called a fictitious name, assumed name, …

If you’re eager to understand the value of registering a DBA in New Jersey and the steps required, you’re in the right place. A DBA, which stands for “doing business as,” allows business owners to use a different name for marketing, sales, and legal purposes. In various states, it’s sometimes called a fictitious name, assumed …

Curious about why a DBA registration matters in South Carolina and how to get it done? You’re in the right place. A DBA, which stands for “doing business as,” allows you to operate your business under a different name for purposes like marketing, sales, and legal dealings. It might be called a fictitious name, assumed …

If you are interested in comprehending the importance of a DBA in Georgia and the procedure for registering it, then you’ve found the right source. A GA DBA, which stands for “doing business as” allows entrepreneurs to adopt an alternative business name for advertising, commerce, and legal activities. In certain states, this alternate name may …